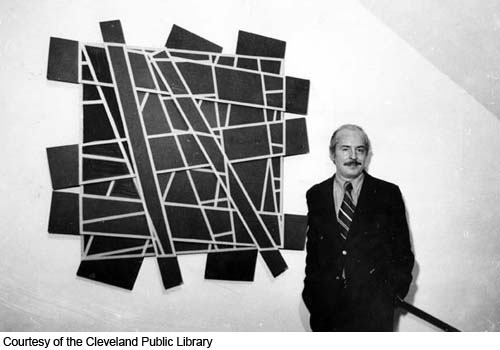

Ed Mieczkowski, Painter 1996 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR VISUAL ARTS

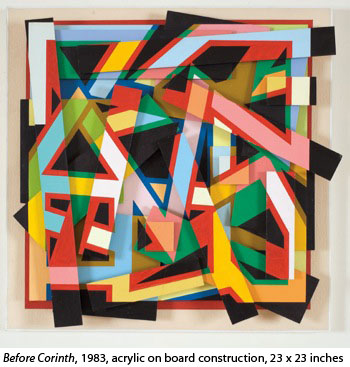

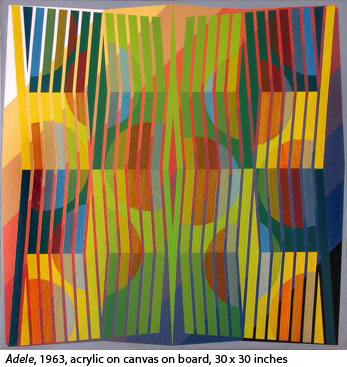

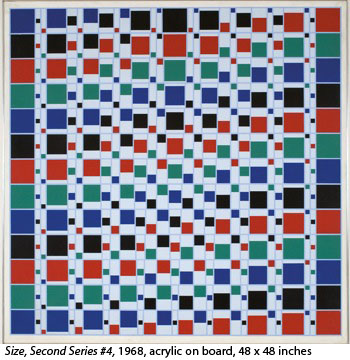

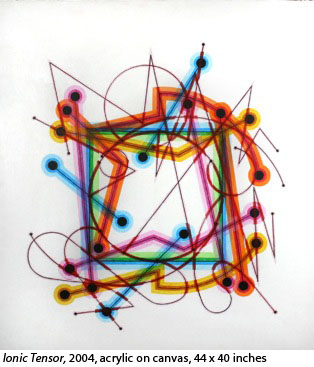

Ironically, it was Mieczkowski himself who had sought a low-profile career, so he could pursue his work undistracted by the frantic trends and shifting tastes of the New York art set. In 1959, when Abstract Expressionism was the rage, the then 29-year-old artist (born in 1929) and first year instructor at the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) had quietly joined with a group of other young, mostly Cleveland-based artists who were interested in following their own shared interest in exploring the interplay of color, intensity and geometric forms and their effect on the perception of the viewer. Fame and material success, Mieczkowski (pronounced: Mitch-KOW-skee) and his friends agreed, was not their goal. They called themselves the Anonima group. But just five years later, in 1964, they were being heralded by Time magazine as the beginning of something called “Op [for Optical] Art”, with Mieczkowski’s mesmerizing Adele’s Class Ring as Exhibit A. The following year saw his work featured—along with that of fellow CIA faculty members Julian Stanczak and Frank Hewitt and alumnus Richard Anuszkiewicz—in a history-making show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), The Responsive Eye. In contrast to the raw, freewheeling feel of Abstract Expressionism, their work was geometrically elegant, layered, carefully planned and often deliciously complex. It made the viewer aware of his/her own participation in the act of creation at a visceral level. Mieczkowski once told artist/art writer Douglas Max Utter that he was fascinated by telomeres, tiny attachments at the end of a DNA strand that to him conveyed “optimism and energy.” Born in Pittsburgh in 1929 of Polish parents, Mieczkowski seems to have taken particular satisfaction in the 1966 exhibition of his work at the new Galeria Foksal (“one of the most courageous galleries of the twentieth century”) in what was then communist Warsaw. He was recognized the same year with the Cleveland Arts Prize. The rage for “Op Art”—Mieczkowski has always disliked the term—soon gave way, like other artistic gospels of the moment taken up by the trend-chasing Manhattan art elite (see Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word), and became, in its turn, last year’s news. Ed Mieczkowski would spend the next three decades dividing his time between New York, where he taught at the Pratt Institute and the Cooper Union, and the Cleveland Institute of Art (where he had earned his own BFA in 1957 before taking a master’s degree from Carnegie Mellon), sharing his insights with gifted students like Joshua Kosuth and April Gornik. All the while pursuing his own vision in the quiet of his Euclid Avenue studio, which he lovingly dubbed “the Idea Garage.”

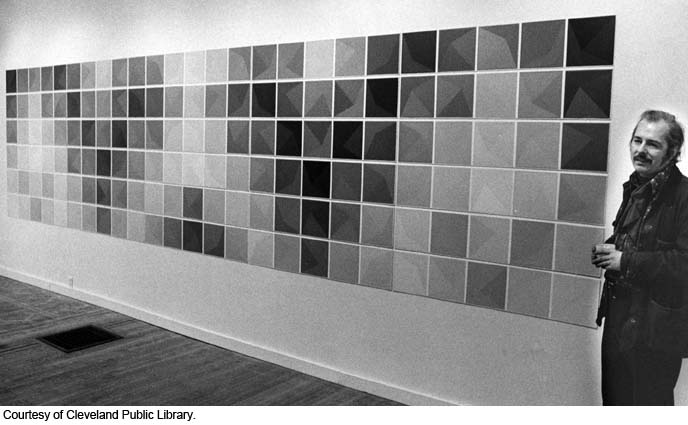

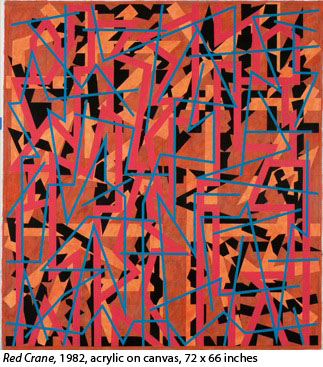

Plain Dealer critic Steve Litt, reviewing a show of new work by the artist the following June at Tregoning Fine Art in Chagrin Falls, marveled at the way Mieczkowski’s paintings “seem to be a source of light.” One glowed, he said, “like blue neon”; another felt “hot and spicy”; while a third, titled Furnace II—alive with “hot yellows . . . midnight blues . . . [and] heavily saturated maroons”—appeared to pulse like “molten steel.” Perhaps Mieczkowski’s best known, or at least most accessible, local work is the large mural, Sommer’s Sun, commissioned in 1979 for the main reading room of the Cleveland Public Library. This modern-day tondo (a shape loved by Italian Renaissance painters) takes its colors, theme and geometrical cues from the nearby mural done in the 1930s by Cleveland artist William Sommer—the red, stylized rays of its setting sun and its view of Public Square, low buildings and intersecting streets that is all angles and bold primary colors. Sommer’s Sun seems to warm and stimulate the activity in the room. It reminds us that the cool detachment of the modern intellect does not negate or replace the hot truth of our bodies, and that the perceiver, the thing perceived and the experience of perception may all finally be, as William James thought, one thing. —Dennis Dooley Please visit www.lewallencontemporary.com All photos, unless noted otherwise, courtesy of LewAllen Contemporary – the gallery

|

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

In 2004, as Ed Mieczkowski lay near death in a hospital in Houston with an aortic aneurism, a “rescue caravan” of cars and trucks was

rushing to his Cleveland studio, where bulldozers were preparing to

demolish the building on which the artist’s lease had expired. Inside

were more than 100 paintings, drawings and constructions.

Irreplaceable, commercially forgotten.

In 2004, as Ed Mieczkowski lay near death in a hospital in Houston with an aortic aneurism, a “rescue caravan” of cars and trucks was

rushing to his Cleveland studio, where bulldozers were preparing to

demolish the building on which the artist’s lease had expired. Inside

were more than 100 paintings, drawings and constructions.

Irreplaceable, commercially forgotten.  The

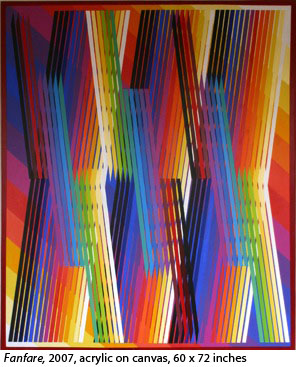

results, discovered by west coast art dealer Kenneth Marvel on a

serendipitous visit to Cleveland, were to be laid before the public in

2006 in a four-decade retrospective of Mieczkowski’s work at the

LewAllen Contemporary Gallery in Sante Fe, New Mexico. Visual Paradox: Transforming Perception stunned a whole new generation of art lovers, who paid as much as

$45,000 for a single painting. Mieczkowski, who had continued to paint

even after retiring in 1998 to Huntington Beach, California, was still

finding new delights in the act of perception that he was eager to

share with us.

The

results, discovered by west coast art dealer Kenneth Marvel on a

serendipitous visit to Cleveland, were to be laid before the public in

2006 in a four-decade retrospective of Mieczkowski’s work at the

LewAllen Contemporary Gallery in Sante Fe, New Mexico. Visual Paradox: Transforming Perception stunned a whole new generation of art lovers, who paid as much as

$45,000 for a single painting. Mieczkowski, who had continued to paint

even after retiring in 1998 to Huntington Beach, California, was still

finding new delights in the act of perception that he was eager to

share with us.