Ernestine and Malcolm Brown, Pioneering Gallery Owners and Art Educators 1994 SPECIAL CITATION FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE TO THE ARTS

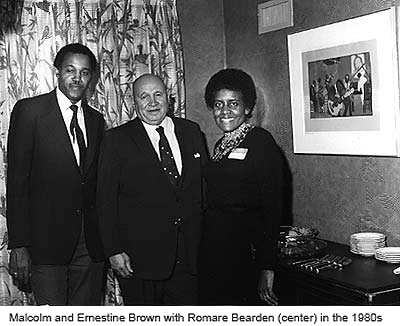

Until its closing in 2011, the Malcolm Brown Gallery showcased African-American artists, past and present, with Malcolm Brown (who had earned his master's degree in art history from Case Western Reserve University in 1969), taking his turn beside other nationally prominent black artists whose work had not been seen before in the region. These solo and group exhibitions, often supplemented by gallery talks and book signings, arguably did more than any other local institution's exhibitions to give area art lovers the opportunity to view, appreciate and collect fine art by African Americans. Among those who came to look and learn: two generations of students shepherded by Brown himself, who taught art for 32 years in the Shaker Heights public schools (1969–2000) and evening classes for 12 years at the Cleveland Institute of Art (1970–1982), while creating, showing and selling his own work here and around the U.S. The gallery also did much to restore some lost pages in the history of American art. A 1993 exhibition featured 15 stone and bronze sculptures, including a bust of Duke Ellington, by the 93-year-old Selma Burke. Burke, who first won attention in the 1930s in that explosion of art, literature and music known as the Harlem Renaissance, had later married poet Claude McKay, gallery-goers learned, and traveled to Europe to study with Henri Matisse and Aristide Maillol. She is best known for her bronze portrait plaque of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, created from life in 1944, while she was working as a truck driver in a New York naval yard. This is the portrait featured on the “Roosevelt” dime. In 1994. the Malcolm Brown Gallery displayed the playful jazz-inspired work of Moe Brooker, a painter (and Cleveland Arts Prize winner) who had taught at the Cleveland Institute of Art from 1976 to 1985. The next year brought the second of three exhibitions of dazzling quilts by the Cincinnati artist Carolyn Mazloomi, whose work had been shown at the Corcoran Gallery and the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., but until the Brown Gallery shows had never been seen in Cleveland. And 1997 brought together 25 drawings, prints and collages spanning three decades by the legendary Romare Bearden (1912–1988). Departing once again from the usual practice of commercial galleries, which tend to display only work that is for sale, gallery director Ernestine Brown cajoled private collectors to lend some of their favorite pieces for the occasion. The result, wrote Plain Dealer critic Steve Litt, was “scrumptious.” Other prominent African-American artists exhibited by the Malcolm Brown Gallery have included Elizabeth Catlett, Lamar Briggs, Ed Dwight and Hughie Lee-Smith, the most famous black American artist ever to come out of Cleveland. Though the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing when he was coming of age on East 105th Street, Lee-Smith had had no local role models. He honed his craft under the watchful eyes of Carl Gaertner, Rolf Stoll and Henry Keller at the Cleveland School of Art (CSA, now the Cleveland Institute of Art), becoming only the second African-American to graduate from CSA and the second elected to membership in the National Academy of Design in New York. Hughie Lee-Smith (who had been given solo shows in 1984 and 1996) was included, along with Oberlin-born Charles Salee (the first black graduate of CSA) and Cleveland muralist Elmer Brown (whose 1942 Mural for Freedom still graces the auditorium of the City Club of Cleveland) in an ambitious exhibition mounted by the Malcolm Brown Gallery in February 2001. The show consisted of 30 pieces by 14 African-American artists whose careers had been fostered by the Works Progress Administration during the Depression. Here, side-by-side for perhaps the first time, was work by the great Jacob Lawrence, Horace Pippin, Ernest Alexander, Fred Jones, Margaret T. Burroughs, William Carter, Frank Neal, E. C. Nixon, James Porter, Charles Sebree, Brown, Sallee and Charles White. The gallery commissioned Alfred Bright of Youngstown State University to write a catalogue. The Browns have also shown work by famed African batik artist Nike Olaniyi, Cuban painter Ramon Carulla and important non-African American artists (a 1983 tapestry show included designs by Philip Pearlstein, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Motherwell). But their primary commitment has always been to what the Cleveland Arts Prize called their “shared dream”: to bring the rich heritage of African-American art and African-inspired design into people's lives and homes–in all its stunning variety. For Africa, as author Sharne Algotsson (The Spirit of African Design) told a standing-room crowd at the Malcolm Brown Gallery in 1999, is “not just one country,” but a land of “many countries and languages.” Thanks to Malcolm and Ernestine Brown, northeastern Ohioans now have a sense of that richness. —Dennis Dooley |

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

A survey taken by the American Art Dealers Association

in the early 1980s revealed that 75 percent of contemporary art

galleries failed within the first five years. But those odds did not

dissuade Malcolm and Ernestine Brown from opening the Malcolm Brown

Gallery in 1980 in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights. Nor were

they daunted by the fact that few galleries in the country specialized

in showing the work of African-American artists. Brown, himself an

aspiring young watercolorist from Charlottesville, Virginia, had

learned first hand about the neglect of black artists by mainstream

commercial galleries. And he and his wife, Ernestine, a former business

teacher from Youngstown, Ohio, who had met when she was a graduate

student at Boston University, were determined to change that picture.

A survey taken by the American Art Dealers Association

in the early 1980s revealed that 75 percent of contemporary art

galleries failed within the first five years. But those odds did not

dissuade Malcolm and Ernestine Brown from opening the Malcolm Brown

Gallery in 1980 in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights. Nor were

they daunted by the fact that few galleries in the country specialized

in showing the work of African-American artists. Brown, himself an

aspiring young watercolorist from Charlottesville, Virginia, had

learned first hand about the neglect of black artists by mainstream

commercial galleries. And he and his wife, Ernestine, a former business

teacher from Youngstown, Ohio, who had met when she was a graduate

student at Boston University, were determined to change that picture.